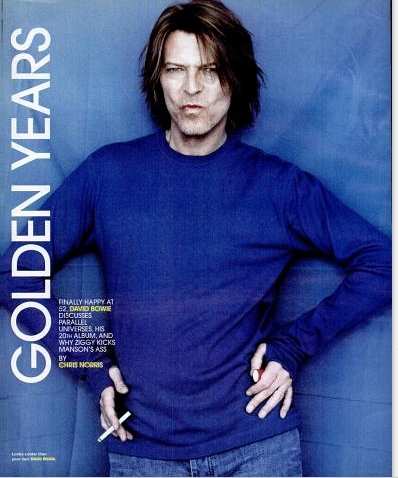

Golden Years

(Spin, 1999)

Oh, the things I could tell you,” David Bowie taunts an intimate studio audience assembled for a taping of VH1’s concert-and-anecdote series "Storytellers." The crowd gets just one off-camera vignette (something about a Monty Python member’s lust for guitarist Mick Ronson), but everyone is clearly agog over the lightly mascara’d 52-year-old raconteur with the chestnut shag and designer hoodie. Bowie, nearly the only cool thing to come from the ‘70s, is even more impressive seen today. When pundits were just beginning to debate issues like gender and authenticity, Bowie was already out there in a dress proclaiming his own artificiality. While current musicians are still figuring out how to expand into business and film, he's fully diversified: singer, painter, actor, Internet mogul, Britain’s richest pop singer. Two days after the taping, Bowie makes one thing abundantly clear: The former king of excess is now the most well adjusted rock star ever.

What was it like to film a sort of cabaret-style survey of you entire career? So many personas and styles—did it get confusing?

I wasn’t’ sure if I was doing songs or stand-up. Not that I minded. There’s a British thing where rock singers and comedians are envious of each other’s careers. I also think that shtick is an essential part of British rock, a slightly vulgarized idea of integrity. Kind of a [singing tune to “Shave and a Haircut” ] "dah, dah-dah, duh-duh. duh-duh” at the end of everything. It makes the Small Faces. It makes Blur. There’s a sense of tastelessness that keeps coming through.

During Storytellers, you mentioned meeting with late-60s activist Abbie Hoffman.

Yes, it was a few months before he came out of hiding [in 1980]. For some reason he was fixated on talking to me, and I got a note that he wanted to meet me at this divey restaurant in New York. He liked my material, although some of this seemed to be about pulling rank and meeting David Bowie [laughs]. I was gaga. This was the leader of the Yippies. This was someone who knew Huey Newton and Bobby Seal and Eldridge Cleaver. This was real American history.

On the show, you say that 1976’s Station to Station came from one of the darkest periods in your life. What was going on?

At the time, I had this insatiable appetite for magic, mysticism, and alchemy—fired by my ever-increasing use of drugs. I think I’d replaced a real existence with a parallel mystical one in my mind. I was slipping into the delusional. I was exceptionally lucky that it took a positive turn. If I had not taken another path, I am quite certain that I would not have seen the ‘80s

Your new album, hours…, is also quite dark—full of brooding songs about loss, regret, and reaching out to someone who’s not there.

I wish I could say I’m dragging up this great shadow in my soul, but I’m really, rally happy. What happened was I was approached by a game manufacturer and they asked if I would do some music for a new game called Nomad Soul. I said I’d love to write something, but I won't write game music. The one thing I don’t like about games is that the characters are so two-dimensional. [Feigns a robotic voice] “I will kill you now. I will be reincarnated.” I said, “Let me write something that has an emotional engine to it. Treat it as though it were a movie.” They asked if I would be a character, I said, “Only if I’m 24.”That got me thinking about the difference between the young David Bowie and the older one. What’s it like for a 50-year-old looking back on his past? What are some of the things that go through the mind of someone my age when maybe things haven’t worked out for him? There is a sense of doubt, of “if only I could do it over again.” That’s what I harnessed.

Your last record [1997’s Earthling] played around a lot with electronic beats, but this one is a lot more traditional.

I would love to make another album that touches on that which is absolutely current, focusing on the atmosphere and Sonics rather than the lyrics. But that seemed too obvious and done to death for this project. The future is not only going to be about hard-edged people with metal faces. There will be broken hearts in the future.

You knew very early on the degree to which rock is about fabrication and artifice—and how to thrive in that world, even though it’s destroyed so many others.

Maybe it’s because it came out of a simplistic idea that rock was not my lifestyle. I never for one minute bought into the idea that I was born to be a rock star. My natural inclination was to shift in and out. Also, it was very apparent to me that the world was working in a way that information was moving from genre to genre at an increasing speed. The ‘70s were the beginning of the 21st century. There was the idea that there were no absolutes, that things were starting to fragment. We were aware for the first time that we were living in chaos. And we accepted it, believed that it was a more rational way to understand the Earth. There was this sense that the faster we got comfortable with the idea of fragmentation and chaos, the faster we would be able to evolve to the next place.

Did you see film director Todd Haynes’ ‘70s glam-rock homage, Velvet Goldmine?

Yes, and I think that if he had made it a completely gay movie it would have been much better. The gay areas were something he handled very well. The rest of it was pure bollocks. For me it felt like the early ‘80s—Steve Strange, Adam Ant, Boy George, that whole mannequin thing. Glam wasn’t like that at all. It was Woolworth’s. Woolworth’s posing as Jean Genet. The ideal collision of vulgarity and high-mindedness. He didn’t get it.

Was it disconcerting to watch Jonathan Rhys Meyers play a character [Brian Slade] that is obviously based on you?

I didn’t think he was remotely like me. He was a pretty-looking boy, but I didn’t notice if he had a personality. I really hope I was never like that.

You wouldn’t let Haynes use your songs on the soundtrack because you were working on a glam-era piece of your own.

Yes, and now the Ziggy [Stardust] project is a three-headed hydra. It’s going to be a movie, a theatrical production, and an Internet piece. The theater piece will be more internal, more reflective of the immediate repercussions of Ziggy and his effect on the people around him. The film will be the audience’s perception of Ziggy’s life. And the Internet piece will be pure fun, with hypertext links so you can find out who his mum was and things like that. I’m going to include an old song called “Blackhole Kids,” which is fabulous. I have no idea why it wasn’t on the original album. Maybe I forgot.

What’s your favorite Bowie era

?It sounds disingenuous, but I really feel like this one is my favorite, because my personal, emotional, and spiritual life is so buoyant again. Drink, drugs, and all those things are not part of my life.

What do you think of this era’s grand rock conceptualist, Marilyn Manson? His glam incarnation owed more than a slight debt to you. Except for the breasts.

I don’t mind him. But I do find him incredibly American in his approach to what I was doing. Very purist. What I did was far more open-ended. You could take on what Ziggy was about and completely make it your own. What Manson does is a strong statement, but a singular one and not very interesting. I would say Trent Reznor has more longevity. He’ll be around for a very long time.

How 'bout that Puff Daddy song “Been Around the World,” sampling “Let’s Dance”?

[Makes a face.] Made me some money.

Is it hard, balancing art and commerce?

I’m not an obscurantist, that is not my motivation. In fact, I love it when people understand what I’m going—and don’t fuck it up. I don't think much of what I do is that complicated; it’s just not in the mainstream. It’s a dirty job but somebody’s got to do it

Do you have your old costumes in a close somewhere?

I …have…everything.